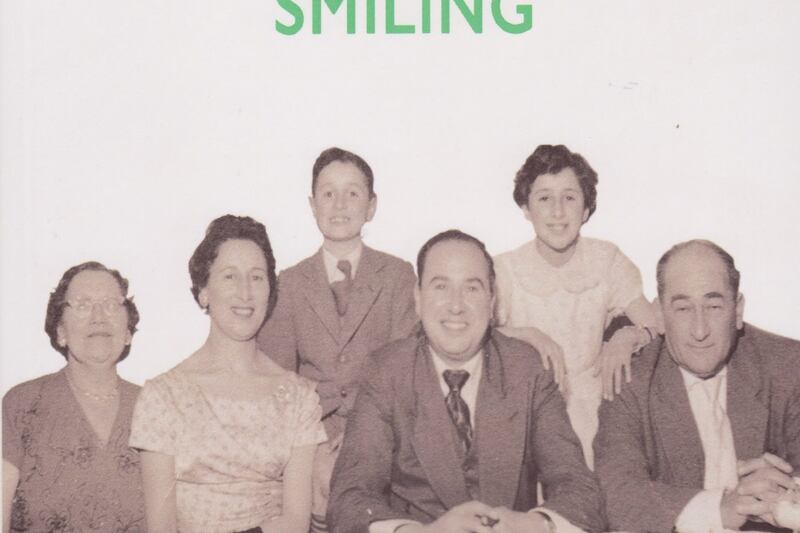

About the book

Anne Lapedus Brest writes with exquisite empathy for herself and others as she relives her carefree life growing up in Ireland. She retells the anguish of her dad’s ophthalmologist offices burning down and of children at her school telling her her parents had died in the fire. Her dad’s office had burnt down but her parents were alive. This taunting triggered a deep-seated anxiety in Brest.

Anne emigrated to South Africa at the age of 14 during the height of apartheid and she found the laws incomprehensible.

She writes about starting over, dealing with a school bully, her dad’s depression and untimely death, her friendships and family and falling in love for the first time.

EXTRACT

THE SOUTH AFRICAN LIFE

Eunice belonged to her own church called “Apostolic” and would go off every Sunday in a huge blue cloak with a big white cross stitched onto the back of it. Sometimes she had her church meetings in her room, and she would sing with her friends. Ma would send in Lecol and sandwiches and biscuits, Robert and I would sit by the back door listening to them singing, enthralled.

Their rich and melodious voices would rise and fall, their harmonies were something so beautiful, I had not heard anything like it before, and the men have rich beautiful deep voices, and the women have strong clear voices all blending so beautifully together.

Eunice made our school lunches, polished our shoes, did the cooking, and washed the windows. We knew she had two small children from a little framed photograph in her bedroom, but other than that we knew so little about her. When Ma would go to the OK Bazaars to buy food, Eunice would never mention that sugar was finished, as long as there was still one tea spoon of sugar in the jar - that meant the sugar was not finished. It took us years to get used to that. Our ironing lady was a Xhosa named Catherine. She came from the Transkei in the Cape.

“You give-eh me schooleh dress-eh, and me, I iron-eh for you”. African people are not allowed to be in the cities unless they are working. There is a “curfew” for them to be off the streets at a certain time. They have to have a “Pass” to show they are working for an employer. Eunice has a Passbook, and she calls it a “Dompas” but at that time I wasn’t yet aware what it meant nor the horrors associated with Africans not having their Passbook on their person at all times.

Our belongings had arrived from Ireland in a “lift”, a few months after we moved into Becker Street. Huge crates made of rough wood, and all of us help with the unpacking. Ma says we keep them as something to sit on, as we had absolutely no furniture at all. They were not comfortable and we got splinters from them, but Ma said it wouldn’t be for long. Just until Da got on his feet.

Da had a great job at Selwyn Super, an optical shop in the Noord Street station. He loved it, went in every morning without fail, he was in great form all the time, and he and Ma feverishly wrote letters to the family telling them everything about our new lives. Ma lands herself a wonderful job with “Springbok Safaris” in Eloff Street corner Commissioner, working for Bill Olds, the owner, and she learns how to handle tours and the tourists. She was very good and very efficient and Mr. Olds gives her an increase before she even gets her first salary cheque. She comes home with brochures and pamphlets of wonderful places around South Africa, and beyond, the Garden Route, Durban, The Eastern Transvaal, and outside South Africa, Rhodesia and the Victoria Falls, Swaziland, Basutoland, South West Africa. The Victoria Falls look spectacular.

The “new life” Da promised us, was really great. Da bought us new furniture, slowly but surely. A lovely yellow melamine kitchen table and chairs to match the melamine cupboards in our kitchen. Some armchairs for the front room, or lounge as they call it here. The house is taking shape, lovely bedspreads now on our beds and our ornaments are on the mantelpiece, and pictures are up on the walls. I love my bedroom. I have a small record player in it and I have started buying records with pocket money Da gives me. The first few months had been hard, we had to make do, but now our little house is perfect.

Jenny comes home with me one day after school. I tell her about the boat trip over, and how hard it was to leave Dublin, and all the time she is saying “Shame, Annie-get-your-Gun, shame hey?” She tells me her Mom works as a hairdresser and sometimes she has to stay very late at work, or even go away to work in hair salons out of Johannesburg, and how hard she has to work to keep their little family going now that they are all living together again as a family. And her Mom being sick and in and out of hospital a lot of the time it is so hard for the family. She said that the twins had hardly known the older children by the time they had all moved from various family homes in Bertrams back into their new home in Bellevue East.

“But what is actually wrong with your Mom, Jenny, is it her heart?” I asked her one day. “No it isn’t, Annie, it’s not her heart.” She didn’t say more, and I didn’t ask ~ but I did want to know, because whatever it was, it still kept Jenny and Adelaide away from school. Sometimes it was a day, sometimes more.

Jenny and I love tanning. We spend weekends at the Yeoville Baths together. We can talk and talk for hours, or we can just lie reading our books and not talk at all. Sometimes we lie on our backs and listen to the music on peoples’ transistor radios. One day some girl there playfully teased me and says that I must be using “Tanorama” which was a kind of fake-tan girls used, as my legs were so brown. I started to laugh but Jenny almost attacked them. She was furious. “Don’t you dare say anything about my friend’s tan, hey?” They backed off immediately and I asked her what that was all about, as I had been flattered by their assumption, it meant I had a good tan. “I suppose so, Annie-Get-Your-Gun, you right, hey, but if she had said that to me, I would have gone mad, but it’s different for you.” I wasn’t sure why it was different, but I kept quiet.

People are still asking me how I can be Irish and Jewish. “How can you be Jewish if you come from Ireland?” “T never heard of an Irish Jew.” “Have you not?” My answer was always the same. “Well, just because you haven’t heard of Irish Jews, doesn’t mean that they don’t exist, poephol!” I loved throwing in that word, and though it is a playful insult, they laughed when I said it, and regarded me as one of them.

Some of the “in” girls would also ask me about Ireland, and if we have cars there or if we went by horse and cart. But they asked me in fun, not like Helena used to do, and now it didn’t upset me at all, I loved to talk to them about Ireland. I missed Ireland, and longed for the day I could go back and visit everyone again. But the longer I was in South Africa, the further away Ireland started to become. It was like another life. As though a million light years were in between the time we left and now. But Pop and Granma were in special places in my heart, and my soul. I missed them and little Fluffy terribly.

When Irish Eyes Are Not Smiling is published by J Doubled Publicity. Extract provided by Janine Daniels.

Would you like to comment on this article?

Sign up (it's quick and free) or sign in now.

Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.